Greek feta, Government Protections, and Cheese Pie

- sc

- Dec 28, 2019

- 6 min read

**************

Me to Lauren upon our arrival in Athens: “I’m excited about the food! Especially the Greek Salads.”

Lauren: “Ugh. But I hate feta. Feta is so dry and tasteless.”

*** 5 hours later at a Greek cooking class ***

Me: “I wonder what this cheese is? It looks like feta, but it is almost like mozzarella it is so creamy.”

Lauren, tasting it: “Definitely not feta. This is delicious.”

Cooking instructor: “Yes, that is feta…” and proceeds to explain the difference between what we, as Americans, think of feta, and what Greek feta actually is.

Lauren and me at every meal over the next week: “Greek salad with feta, please.”

**************

Traditional Greek feta is made from sheep and goat’s milk. To be even more technical, for something to be Greek feta it must be at least 70% sheep’s milk, and the rest must be goat’s milk. Additionally, it must follow a particular process for production and be produced in certain regions of Greece. In the U.S. “feta” is made from cow’s milk and the process of producing it is sped up. This creates the chalky, crumbly taste you are likely imagining. The difference in milk type and production process means that you can hardly even compare the stuff they throw on Greek salads in the U.S. to what you get in Greece. In fact, rather than just getting crumbles of feta, in Greece you get a large hunk of feta on top of your salad. If you ever get a Greek salad in Greece with crumbled feta, that meant they were using leftover or reserve feta. The good places would never do this. (This Cook’s Illustrated article goes into a little more detail about the differences in the way it is made.)

How does this story relate to economics? Well, while in the U.S. you can still buy products called “feta” that are not made in Greece or produced the way the Greeks do it, that is not the case in Europe. In 2002, feta became designated as a PDO, or Protected Designation of Origin. So just like something called Champagne can only produced in Champagne, France, in Europe you can only sell something called feta if it is produced in Greece. Further, it must be produced in specific areas of Greece using the proper procedures and with the correct ratio of sheep and goat’s milk.

Designating Greek feta as a PDO was not a smooth process. Other European companies complained that feta did not come from a specific location in Greece (like Champagne) but just referred to a production process. One of the rebuttal arguments was that European producers of “feta” often had a Greek flag, or some reference to Greece on their container, indicating that they understood that feta was associated with Greece. The designation of Greek feta as a PDO was finalized in 2005. European cheese companies can still produce their cheese that is similar to Greek feta, but they must now call it something more generic, like white cheese.

In essence, the European Union has given Greek feta producers a monopoly over producing feta. Why? Well let’s think back to our discussion on patents. Patents allow the firm who researched and developed something to have sole rights to producing it. This protection allows the company to have the opportunity to turn a profit, or at least potentially cover their research and development costs. For Greece with Greek feta, a PDO gives producers in the country that created and made the cheese famous an opportunity to profit from it without outside competition. For an economy that is struggling like Greece, it is especially helpful.

What about other countries outside of the EU? Can they sell products called feta? Under the CETA trade agreement between the E.U. and Canada, Canadian cheese producers cannot call anything Greek feta or include a Greek related image if it wasn’t produced in Greece. For feta cheese producers in Canada who had been producing for a while, they now much call their products “feta-type cheese” or “feta-imitation cheese”. https://thegreekobserver.com/greece/article/27064/ceta-trade-treaty-benefit-greek-exporters-feta/

The E.U. similarly established an agreement with China such that China cannot sell fake feta under the feta name (and similarly the E.U. cannot sell some Chinese products under their Chinese name). https://greece.greekreporter.com/2019/11/06/greek-feta-cheese-ouzo-to-receive-protection-from-counterfeits-in-china/

How has this protection of Greek feta impacted the exportation of feta from Greece?

Looking at the exports of “Dairy products, eggs, honey, edible products,” from Greece, there has been a steady increase after 2002 with a larger increase after 2005.

(also see below a screen shot from The Observatory of Economic Complexity https://oec.world/en/visualize/stacked/hs92/export/grc/all/show/1995.2017)

According to this article, the importation of Greek feta to the UK increased 214% between 2008 and 2018. The author of the article attributes this spike to a change in demand with an increased desire for Mediterranean food in the United Kingdom. Now, it’s important to be clear that I (nor the author of the article about the UK) cannot place a single reason for the increased exportation of Greek feta. Is it changes in demand for Mediterranean food? Or is the PDO protection? Rather than a discussion of protections, this post could also be a lesson on the importance in the difference of correlation and causation. Is the PDO protection correlated with a rise in Greek exports of cheese? Yes. Is it causing the rise? Maybe? Without more detailed data and a clean identification strategy, I cannot answer that question. In other words, I do not know the counterfactual. If the PDO had not been placed, would this rise still have occurred? I’m pretty confident, however, the PDO did not hurt the rise in Greek feta consumption across Europe.

So, back to the U.S. I bet you’re wanting to see for yourself if Greek feta is actually good. There is currently no agreement between the US and the EU restricting the sale of white cheese under the name of feta in the US. Never fear, you can buy Greek feta in the U.S., but make sure it says “Greek feta,” was produced in Greece, and has at least 70% sheep’s milk. Another tip is that it will also be more expensive than your just “feta” knock-offs. On a positive note, while the U.S. has not committed to only calling products feta if they are produced in Greece, Greek feta has not been hit by import tariffs. This would only serve to increase the price of the delicious, creamy, heavenly Greek feta.

Here is a really good article on the history of feta: https://www.greekgastronomyguide.gr/en/greek-feta-cheese-product/

Exports of feta cheese (2013 – I do not see their sources for this information): https://www.greek-feta-cheese.com/market.html

The European Commission is currently taking Denmark to court over the issue, as there are companies in Denmark selling “feta.” https://www.politico.eu/article/commission-takes-denmark-to-court-over-fake-feta-cheese/

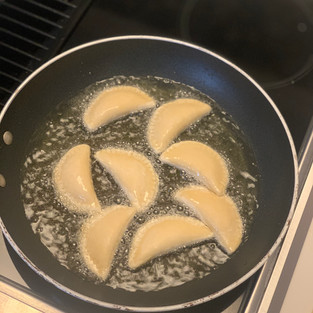

Fried Cheese Pie

I spent a few weeks with some students in Greece where we worked at a refugee camp. One of the perks of the trips was that we ate at this delicious Greek restaurant every night. We loved our waiter Stelios, and he was always suggesting new things for us to try. My personal favorite was the cheese pie. A delicious fried bread with feta cheese inside. The last week we were there, I’m pretty sure we ordered it every night. Yum. One of the Greeks we worked for recommended putting some honey on it. Wow! Even better. The perfect dessert. So, I recommend this as an appetizer, along with your meal, or with honey for your dessert. Enjoy! Oh, and make sure you use real Greek feta PDO for this and not the imitation junk.

** They also have a cheese pie in Greece that is not fried. It’s more similar to their spinach pie made with phyllo dough and they serve it at breakfast. That cheese pie is good. But, to me, this kind is better.

Dough (dough is from a baking class I took at the Greek Kitchen in Athens):

2 cups all-purpose flour

2 Tbsp. olive oil

1/4 cup Greek yogurt (I used Fage)

~ 1 Tbsp. water

Mix together the flour, olive oil, and Greek yogurt. Add 1 Tbsp. of water. If still too dry, add a little more water. Using your hands, combine your dough. Knead until it is smooth. Let rest while you combine the filling.

Filling:

1/2 pound real Greek feta

1/4-1/2 of an egg, slightly whisked

1 garlic clove chopped up (optional)

Crumble up your feta. Add the egg and garlic (if using).

Roll out the dough. Using a round cookie cutter, cut out the dough. You can really make whatever size you want. They can be large or small.

Put a little filling into each circle. Fold up the circles. Seal the pies with your hands. Using a fork, you can ensure that they are really sealed.

Heat vegetable oil in skillet. Wait until the oil hits up. You can put a small piece of dough in the oil. If bubbles come up around the dough, it's ready to go. When ready, place your uncooked pies into the oil. Heat for around 1 minute until brown. Flip to the other side and heat again. Place onto a plate lined with a paper towel.

Wait just a minute for them to cool. Then enjoy - with or without honey!

Comments